The former grounds of our club illustrate the great significance the SK Rapid home ground has. Think briefly about what is necessary to make the new Weststadion rise to a similar cult status as the former home grounds had. Furthermore, pay attention to the values our club represented in the past and try your best to preserve these for the welfare of Rapid.

The historic grounds of the SK Rapid 1897-2014

Tearing down the Gerhard-Hanappi-Stadion, which was opened as the Weststadion in 1977, marked the end of an era. This is why we would like to use this event as an opportunity to shed some light on the former grounds of the SK Rapid and will take a look back at the most important sites in the 117 years of SK Rapid’s history.

“The 1. Wiener Arbeiter Fußball-Club (First Viennese Workers’ Football Club) was founded in September 1898″ is an inaccurate statement in Roland Holzinger’s Rapid-Chronik. Actually, the club had been founded over a year earlier, on July 22, 1897, on the day, on which the foundation was authorized by the police department in charge of registered societies during the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In fact, in September 1898, it was just the first match report that appeared in the press. A great number of Rapidler still believes that this is true, which is why we would like to point that out again.

On March 5, 1898, the Viennese daily newspaper Neues Wiener Abendblatt had published the following: “The 1. Wiener Arbeiter Fußball-Club that set out to introduce football (that has become quite popular in Vienna) to the sport-friendly working class as well, invites all workers seriously interested in sports to join the club that already has good and well-trained players.” For the first match against the Meidlinger Fußballklub, the founding fathers led by Robert Lowe sen. (director of the Böhm hat factory and coach of the »Cricketer«) were only able to scrape together nine players. They managed a 1:1 draw against the Meidlinger who were also playing with only nine players. At the return match, they played 11-a-side and this match ended in a 3:3 draw. The success of the “sports-minded workers” failed to materialize. With a goal difference of 13:107, they were only able to win one of the first 19 matches. On September 18, 1898 a jubilee tournament for Emperor Franz Josef I was played commemorating the 50-year-anniversary of his accession to the throne. It took place at the Hohe Warte, a hill in the 19th district of Vienna, with twelve participating teams and Rapid finished in last place. Probably as well due to the chronic lack of success, the club management strove for changes. The programmatic term “worker” in the club name probably lead to harassment and obstacles in the conservative climate of a time when Karl Lueger was mayor of Vienna and organized labor was considered a threat. The name Sportklub Rapid was proposed by the club secretary Wilhelm Goldschmidt, a Moravian Jew who was deported by the Nazis in 1942 and murdered in an extermination camp. The Berlin-based club Rapide 93 that was playing quite successfully at that time, probably served as model. Due to a press release on January 8, 1899 which covered this renaming, this date is officially considered the founding date of the SCR.

Marked by tough suburban life and a particular class-consciousness in the west of Vienna, Rapid nonetheless kept its proletarian self-confidence and even after changing the name it distanced itself from the bourgeois city. At first, the renaming did not lead to better sporting achievements. In 1899, only two matches ended with a victory. In the first league established by the Fußball-Union (Football Union) in 1900, Rapid played in the second division.

Auf der Schmelz

Until spring 1903, matches were played at the Schmelzer Exercierfeld, a parade ground in the 16th district of Vienna, in front of the still existing Radetzkykaserne barracks. A football field could not really be found there. It was more of a large, cleared area with a hard clay surface that was trampled by horses. The field had to be set up before each match. For two Kronen (former Austrian currency) players bought a string, a few iron bars and a water can filled with lime milk to mark out the pitch. The Rapidler, who still played in red and blue at that time, soon started looking for an alternative to this portable sports field on that uneven ground.

The first own sports ground

The club management managed to obtain a leasehold property for very little money. On May 15, 1903, the new Rapid-Platz was opened next to today’s Meiselmarkt market, which is situated in Rudolfsheim, the 15th district of Vienna. The pitch, which was prepared by the Ur-Rapidler themselves, featured a considerable slope of two meters and was surrounded by a simple barrier. The goal line adjoined the Hütteldorfer Straße and the long side adjoined the Selzergasse. Nowadays, this area has been heavily developed, which of course was not the case back then. A few buildings from the founding period still give us an idea where Rapid held its matches in 1903. A match clock did not exist. The church clock at the Kardinal-Rauscher-Platz provided help and when walking through this area in the 15th district, it is still a reminder of the old days. With the new ground, success slowly started to materialize. On June 21, 1903, Rapid achieved the promotion to the first division with a 3:0 victory in the deciding match against the Deutscher Sportverein (predecessor of the Wiener Sportklub). Rapid has never been relegated again since then. The entrance fee was 80 heller, students paid 40 heller. Despite all efforts of Rudolfsheim’s football youth, it was not possible to enter the ground without paying an entrance fee. Therefore, the wooden planks around the ground soon featured a great number of peepholes and the apartment windows were always well attended. Subsequently, the ground was equipped with a small wooden stand and a clubhouse and thanks to great perseverance, the rise of the Sportklub Rapid slowly began.

In 1910, the lease for the ground in Rudolfsheim was unexpectedly terminated by the City of Vienna, as they wanted to build a hay market on the same spot.

Relocation to Hütteldorf

This occurred at a time when Rapid was already facing a sporting and financial crisis. Important players had left the club and the construction of the sports ground in Rudolfsheim had cost the club a lot of money. The executive committee around Alois Hoisbauer, the president at that time, appointed the 23-year-old typesetter Dionys Schönecker as Head of Section. Dionys Schönecker, who once played together with his brother Eduard for Rapid, made the SCR to the most successful club team in Austria.

With a lot of courage and confidence, he relied on a young, unknown team, which used the short passing game, a system that was becoming quite modern. Thus, the club found a way out of the crisis. Since Rapid was left without a home ground after the termination of the sports ground in Rudolfsheim, they had to play all their matches on another club’s ground in the fall of 1911. Rapid was able to achieve a commanding 4:1 victory against the newly founded Amateure, which was a spin-off of the Cricketer and later converted into the Austria. Contrary to the working players of the migrant suburbs, the Amateure had the reputation of an upper middle class City Club committed to money. Not least because of that, the duel became the most important match in Austrian football over the next decades.

Meanwhile, and at a time when people had to cope with poverty and hunger, the executive committee succeeded in finding a new ground. They were able to lease a green space opposite the Hütteldorf brewery from the Hütteldorf parish. Ing. Eduard Schönecker was put in charge of planning the new ground in the city’s green belt. In the meantime, Dionys Schönecker’s older brother had completed his architecture studies. The new ground on the very narrow property was his first large project, which he realized with great skill. In fall 1911, the Universale construction company started construction work according to Schönecker’s plans so that the so-called Pfarrwiese could be opened on April 28, 1912. Apart from the wooden stand for 300 spectators, which was taken along from the sports ground in Rudolfsheim and rebuilt at the Pfarrwiese, there was a gently rising slope, which offered all spectators a good view of the pitch.

On the long side Eduard Schönecker ordered the building of a stand with wooden steps and flying roofs which would protect the fans from wind and weather. So there was a spectator capacity of 4,000 people. Rapid settled well in the noble suburban area and achieved seven league titles in the first ten years playing at the Pfarrwiese.

Rapid’s neighborhood

Daily life, however, took place a few more kilometers into town, where players and officials lived. Taverns, streets, parks and grounds on and around the Schmelz were places of conviviality and a self-determined life in a lively suburb. People living there had many things in common: originating from a poor background marked by the supportive society living in villages and small towns of Bohemia and Moravia, being proud of their advancement as workers, craftsmen and small businesses, which they achieved through their own efforts in their new home: the growing, urban west of Vienna. That welded those people together in the same way as their hard life and their aversion to the “big-headed” citizens living into town on the other side of the Gürtel. Amidst this class-conscious society, the SK Rapid quite quickly became their figurehead. Quite exemplary for this milieu are the Holub and Kochmann families (originally from Bohemia) that were innkeepers, officials and also players (Leopold Nitsch married into the Kochmann family) and formed the heart of the Schmelzer Rapid. The Stefaniesäle, an inn, of the Kochmanns as well as the Café Holub were clubhouse, secretary and a daily meeting place from 1900 until the 1950s.

It was an immigrant area and at that time, the fastest growing part of Vienna. From there, people took the trams 49, 50 and 52 as well as the Vienna Metropolitan Railway to comfortably get to Hütteldorf. If they could afford it, because also the post-war period was dominated by unemployment, economic crisis and inflation. Nevertheless, the Viennese never lost their lust for life and after WWI, football became more and more popular so that the Pfarrwiese soon was not able to cope with the many spectators.

With spectators numbering up to 20,000 people, an extension became necessary and once again Eduard Schönecker was commissioned with the planning. On the south side, a new stand for seating was build out of concrete and wood. The standing area on the north side was equipped with concrete steps and a wooden roof was built on the upper side of the stand. The football field was also widened by five meters. With that, a capacity of 25,000 people was achieved. This was sufficient for “normal” league matches. However, it was not enough for big matches in a Vienna that increasingly became “Europe’s footballing city”. From time to time and for big matches, it was necessary to switch to the ground at the Hohe Warte, where for example, 40,000 fans watched the match against Sportklub in March 1924. For financial reasons, Rapid rejected the proposal of the City of Vienna to move to a planned, huge national stadium in Schönbrunn or in the park of Schönbrunn (today’s Auer-Welsbach-Park). For Rapid, it was preferable to stay in the small and classy sports ground in Hütteldorf, which was already characterized by its unique atmosphere at this time. The Pfarrwiese slowly became a cult location. Inspired by the “Tempo, Magyarók!“ of the Hungarian supporters, the clapping ritual of the Rapidviertelstunde (the last 15 minutes of a match) was born in the 1920s at this place. This clapping ritual became a trademark, which particularly characterizes the will to win and fighting spirit of the SK Rapid.

Highly emotional supporters

At a match against Hakoah (1:1) on September 28, 1924, which was watched by 30,000 spectators according to rapidarchiv.at, things got very heated and volatile. The Viennese newspaper Wiener Sonn- und Montagszeitung reported with outrage: “It is only the merit of referee Schmieger that this match, the highlight of yesterday’s football Sunday, could be finished without any further irregularities.

A part of the crowd seemed to have come to the ground only to kick up a row and to decide the match from the stands. Hütteldorf’s supporters wanted their “revenge” for the last major defeat of their team. As they were not able to stir up the players – because, as professionals they now had too much to lose and had to remain calm – they focused on the referee. The supporters of the Krieauer were not harmless either and were also unsparing with their extensive shouting. Under these circumstances, yesterday’s match at the Rapid ground was quite turbulent at moments. The most popular target for insults remained the referee. It is not an overstatement to note that every important decision made by Schmieger – unless in favor of Rapid – was accompanied by a tremendous and loud protest. […] The behavior of a part of Hütteldorf’s audience, which various away teams have already complained about, may no longer be ignored. […] This fits quite well with the description of the events which mentioned that Schmieger had been insulted and spit at on his way to the dressing room.”

The atmosphere was particularly hectic at derbys. On May 6, 1934, the match was abandoned at a score of 2:2. After a serious foul by an Austrianer, angry supporters invaded the pitch and threw stones and lemonade bottles at the Austrianer.

Austro-facism and National Socialism

After the opening of the Wiener Stadion (1931), big matches (like derbys, Mitropa Cup or other European competitions) were played in the Prater. As of 1933, the political situation again became precarious. In the fascist Ständestaat (cooperative state) under Engelbert Dollfuß, as well as later in the National Socialist regime, the sport experienced many restructuring processes.

Rapid always knew how to adapt to the new circumstances and benefited from the reputation of a “down-to-earth and fighting” club. At the same time, some Rapidler were displaced, murdered or died in the war. In 1938, Rapid won the Tschammer-Pokal, a challenge cup for the German cup victory during the NS era.

At the same time the Nazis invaded the Soviet Union, Rapid won the Großdeutsche Meisterschaft (Greater German Championship) in 1941. Various legends exist about that victory that, however, have never been verified. In addition to the two Jewish NS victims Wilhelm Goldschmidt and Fritz Dünnmann, at least eleven other active and former members of the football section were killed in the war. The Rapid defender Fritz Durlach was sentenced to one year behind bars for torture and abuse as a war criminal.

The glorious 50s

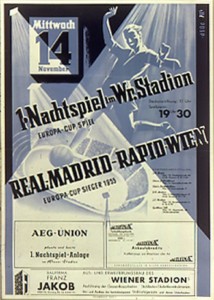

After the war, coach Hans Pesser built the legendary Rapid team of the 50s that was probably the best Rapid of all time and was among the strongest clubs in Europe. The classic line-up of this wonder-team: “Tiger” Walter Zeman, “Wödmasta” Ernst Happel, Max Merkel, Leopold Gernhardt, “Gschropp” Gerhard Hanappi, “Tausendsassa” Franz Golobic, Robert Körner (“Körner I”), Hans Riegler, Robert Dienst, “Mopsl” Erich Probst, Alfred Körner (“Körner II”). The team scored non-stop and for example defeated Arsenal in Bruges by 6:1. The glorious 3:1 victory against Real Madrid in 1956 took place in the Wiener Stadion and for the first time, the match could be held in the evening thanks to new floodlights.

In 1961, there was once again a scandal at the Pfarrwiese. After a wrong decision by the referee, Rapidler invaded the pitch and attacked the Wacker goalkeeper. The match was abandoned and the police doctor could not rule out an internal injury to the goalkeeper Pesser. Even after the abandonment there were fights and the police eventually cleared the ground. As a result, the club was not allowed to play the next three matches on its ground. However, just two weeks later, there were again riots at the semifinals against Benfica in the Prater-Stadion and the match was abandoned as well. “Several thousand young people started demolishing benches after the abandonment and also began removing the roof of the commentator cabin and tried to light a fire with paper. There were fights in the stands as well as on the pitch that had been invaded. The intervening police was attacked with all sorts of objects, including stones. Only when considerable police reinforcements arrived, were they able to clear the pitch and stands.

Goal in the east

The Pfarrwiese featured certain peculiarities that gave the opponents a hard time. A particular specialty was the tunnel, through which the player needed to walk in order to enter the pitch. The tunnel through which players came onto the pitch was one of these peculiarities. It was narrow and dark, and it was discouraging for the players of the away team to have to walk through it. Among other things, the players of Rapid, who entered the tunnel after the away players, shot balls against the tunnel walls in order to frighten the opponents who were in the dark tunnel. Furthermore, it is said that there was a 1.7 meter high iron beam spanning the width of the tunnel on which players of the away team often hit their heads. After his active career, Hans Krankl confessed: “There was no one who went through that tunnel and did not feel a shiver down their spine.”

Legend has it that a goal at the Pfarrwiese was not like any other. During training, they played on the “goal in the east”, which is why this goal was especially feared by the opposing goalkeepers as Rapid players knew every unevenness, every blade of grass there.

The Rapid-Eck (Rapid corner)

To an extent, the origins of the Block West also date back to the Pfarrwiese, which featured the so-called Rapid-Eck at the west ramp in the southern end of the stadium. During the period between WWI and WWII, it was already the place of the loudest and most rabid supporters. This is where the clapping of the Rapid-Viertelstunde began. Moreover, in the early 1970s, the youth fan culture as we know it today started with flags on the west of the Pfarrwiese.

The Pfarrwiese slowly weathered away and whereas football and infrastructure in particular developed according to an international standard abroad, Rapid kept losing ground to European leaders. This is still an issue today. There was a lack of professional training possibilities and floodlights. The number of spectators declined drastically. On January 18, 1956 there were almost 30,000 spectators at the European cup match against Milan. However, in 1973 only 4,000 people watched the match against the same opponent.

Weststadion

In the late 1960s, a plan came up to build a feeder road to the Flötzersteig above the Pfarrwiese. Although this project was discarded due to citizen’s protests, the end of the Pfarrwiese became a certainty. Once again, a Rapidler was commissioned with the planning of a new home ground not far from the old one. Gerhard Hanappi, who studied architecture after a great career as a player, started the project Weststadion for the City of Vienna. The construction began in 1971 on the area of a former market garden. However, the planned opening date of 1974 was delayed enormously. Due to financial reasons various adaptations had to be made. A major modification of Hanappi’s plans was a 90 degree rotation which converted the Weststadion into a windy “bird house”. The first match took place on June 30, 1976. It was the final of the Schülerliga (school league) which was watched by 6,000 people. In the first league match in the Weststadion, Rapid defeated Austria 1:0 with 14,500 spectators in the stands on May 10, 1977. At this time, construction work along the outside area was not completely finished yet, which is why the official opening took place on September 14 with the UEFA-Cup match against Inter Bratislava. Although there was a 1:0 victory, the match went down in history for other reasons. After the match, young Rapidler went on a rampage in the Metropolitan Railway. The emergency brake of one of the trains was pulled and the bulbs of the standing train were removed. It is said that even the rear lights of the wagon were extinguished. The following train hit it with full force. 44 persons were injured and 200 men of the fire department had to rescue trapped people. The young men were arrested and tried in court for acts of vandalism. Experts made the train driver of the following train partially responsible and he received a suspended jail sentence of six months.

Closed in November 1977

Construction of the Weststadion also had a legal aftermath. In November 1977, the new stadium was closed again because of construction defects. It was caused by cracks in one column of the North Stand. Until its repair, Rapid played on different grounds (Sportclub-Platz, Hohe Warte and Horr-Platz). In spring 1978, Rapid even returned to the Pfarrwiese after fans had greatly helped to bring the desolate playing grounds back into shape during winter break. Hardly surprising, it was difficult for the fans to get along with the new concrete block after its reopening at the beginning of the season 1978/79. The cold Weststadion had none of the Pfarrwiese‘s charm.

The long way to a cult location

After Gerhard Hanappi died with only 51 years in 1980, the stadium was renamed after its architect in 1981. One year later, Rapid celebrated its 25th Austrian league title with Hans Krankl, who had returned from Barcelona, and with the midfielder genius Antonin Panenka. In the last match, Wacker Innsbruck was defeated by 5:0. The Gerhard-Hanappi-Stadion was filled far beyond its officially licensed capacity. After the final whistle, the fence in front of the West Stand dropped as if it was made of paper and the fans ran on the pitch. From this day on, Rapidler accepted the Gerhard-Hanappi-Stadion as its home. More league titles followed and especially because of great European matches as against Dynamo Dresden, the Hanappi slowly became a cult location. After reaching the European Cup Winner’s Cup Final in 1985, a new crisis began and the existence of the club was at stake at the beginning of the 90s. The number of spectators was correspondingly weak. For example, in 1988, only 3,800 people came to the celebration of the league title. This time also marked the birth of the Ultras Rapid and subsequently of the Block West as we know it today. Depressed by the sad situation with Rapid and inspired by journeys to Italy, some Rapidler started to establish the Ultra culture in Austria.

With the departure of the strict Binder jun. in 1992, the West Stand was gradually brought to life. It followed a cup victory in 1995 and a league title in 1996 as well as reaching the final of the Cup Winner’s Cup. However, at league matches there were often still only a few thousand spectators.

Block West – simply the best

Andy Marek, who worked as stadium announcer since 1992, played a key role in the following upswing. In 1998, he built up the Klubservice and did important work for the SK Rapid. Nevertheless, the Hanappi-Stadion “aged” quite quickly. Therefore, extensive modernization works became necessary in the early 2000s. The West and East Stands received a roof, the roofs of the South and North Stands were renewed and a VIP garage was built. Therewith, the capacity decreased to 18,500 spectators. Meanwhile, the fan scene continued to evolve and as of 2003, it accounted for a significant part of the fascination of visiting a match.

“Sankt Hanappi“

Rapid experienced a real boom again. As of 2004, the West Stand was sold out with season tickets, which is why a second fan stand developed on the East Stand. With an average number of spectators of almost 17,000, Rapid was the measure of all things in Austria. From the sporting point of view, everything went great as well. In 2005, driven by the fans, Rapid celebrated its 31st league title. In this season, Rapid remained undefeated in the Hanappi-Stadion, which is why coach Josef Hickersberger coined the term “St. Hanappi” (Saint Hanappi). For matches in the group stage of European competitions, Rapid gave up the home advantage because of the great interest of spectators and the Ernst-Happel-Stadion was sold out several times.

In 2008, the Gerhard-Hanappi-Stadion saw Rapid win its last league title. Particularly play-off matches in European competitions as against Partizan, Aston Villa and PAOK have become indelible memories for all time among our generation. The same goes for situations in the years before the stadium was demolished. Given the desolate condition of the Gerhard-Hanappi-Stadion, changes were an urgent necessity. Renovating and adapting would neither have been reasonable nor economical, which is why a new stadium is being built on the same site.

Outlook towards the new Weststadion

Most Rapidler are eagerly awaiting the Weststadion. Fortunately, the new home of the SCR will again be in Hütteldorf. Yet we are not quite sure about what to expect, nor can we tell if any unwanted side effects may come of this. A number of well-known elements of the Gerhard-Hanappi-Stadion have been integrated in the new stadium and will make our former home ground stay in our memory. Changes like a huge VIP and business area, an enlarged distance to the pitch, closed corners as well as the stadium’s uncharacteristic appearance for the city of Vienna have given many Rapidler a reason for pause. Unfortunately, the possibility to build a new home stadium the old-fashioned way without withdrawing from competition is no longer an issue for the SK Rapid in the 21st century. The ongoing commercialization of modern football over the last years has reached its peak with the brand-naming of our stadium. That are circumstances we are already trying to counteract for years now, however, in the end we have to admit that we had not enough to oppose. The difference to our familiar home is huge and many of the moments that shaped our lives as Rapidler will no longer be possible in the future. Whatever the case, it is up to each and every Rapidler – by remembering old values – to make the new Weststadion a place steeped in history, a place in which the Rapidgeist runs true.

This article has already been published in a similar form in Tornados Spezial #34

Sources:

Jakob Rosenberg/Georg Spitaler: Grün-weiß unterm Hakenkreuz. Der Sportklub Rapid im Nationalsozialismus (1938-1945). Wien 2011

Andreas Tröscher/Matthias Marschik/Edgar Schütz: Das große Buch der österreichischen Fußballstadien. Göttingen 2007

Johannes Sachslehner: Schicksalsorte des Sports. Wien-Graz-Klagenfurt 2011

Günther Allinger: Das neue Rapid-Buch. Wien 1977

Edgar Schütz/Domenico Jacono/Matthias Marschik: Alles Derby! 100 Jahre Rapid gegen Austria. Göttingen 2011

Roland Holzinger: Die Chronik 1899-1999. Waidhofen/Thaya 1999

Eric Phillipp: Das Herz von Hütteldorf. In: Ballesterer Ausgabe 94. 2014

Rapideum and personal conversations